What has covid-19 taught us about remote work?

In April 2020, I published a first draft of The Case for Remote Work, which pulled together a lot of the existing academic literature to argue remote work would be much more common in the years ahead, and that this was probably a good thing. I had been working on it for about a year, off and on, but the onset of mass remote work in March due to covid-19 pushed me to finish and begin disseminating it (a final version was published in October).

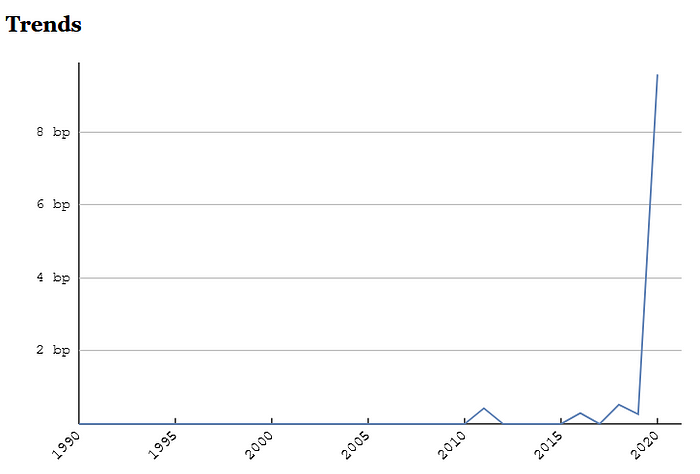

In the 11 months since that April first draft, there has been an explosion of new academic studies on remote work. The following figure charts the annual number of economics working papers in the REPEC depository that include the phrase “remote work” in the title or abstract.

What can we learn from all this new work? After diving into this new literature, here are six lessons I am taking away.

(Aside: if you want to dive in yourself, I recommend starting with Barrero, Bloom and Davis 2020 and Microsoft’s The New Future of Work. Both contain recent, complementary, literature reviews. You’ll see them quoted more than any other study below)

1. Pre-covid studies of remote work have held up

Prior to covid-19, there were a handful of economic studies on remote work. These studies’ conclusions have held up quite well.

First, before covid-19, quasiexperimental and actually experimental research on a life sciences company, call center operators, and patent examiners all found remote work to be more productive than being in the office. Other approaches found more mixed results: firms that switched to offering remote work capabilities experienced small negative productivity effects on average, but with lots of variation across types of firms. Some firms saw positive effects, many saw no change, and some saw adverse effects.

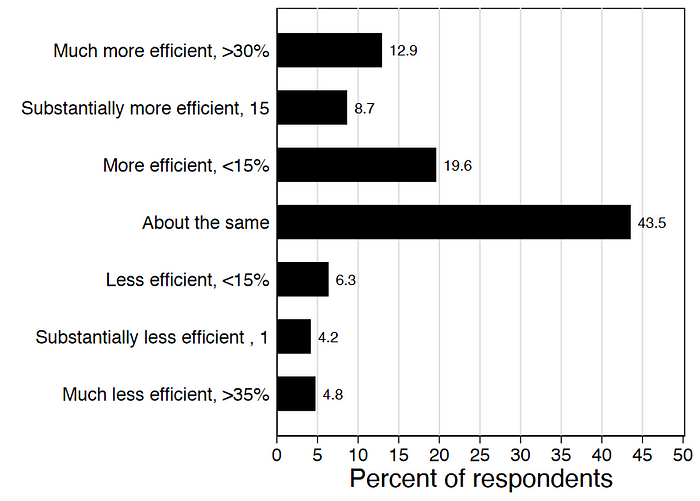

A variety of evidence from 2020 validates these findings. Barrero, Bloom and Davis (2020) report on the results of a large survey (10,000+ US respondents) in August through November that asks about self-reported efficiency of working from home. Fully 41% of respondents think they are more efficient working from home, and 44% think they are about the same. These kinds of results are broadly consistent with many other surveys that find the majority of workers found the same or higher productivity during the forced transition to remote work.

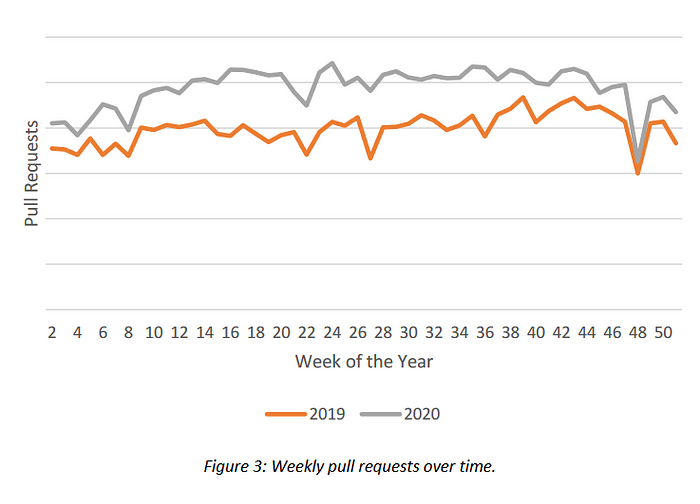

These self-reported assessments are consistent with the smaller number of studies with objective measures of productivity as well. Emmanuel and Harrington (2020) finds calls answered per hour rose by 8–10% when call center operators switched to remote work due to covid-19, relative to workers who were already working remotely and thus unaffected by the change. Notably, this is quite close to Bloom et al. (2015)’s findings that productivity in call centers rose by 13% when workers switched to working from home. At Microsoft, the number of weekly code pull requests shows no significant change around weeks 13–18, when lockdowns were rolling out across the world, as compared to the previous year. Neither did Microsoft observe a decline in other quantitative measures of software engineer productivity (though 38% of software engineers felt less productive).

A second finding from the pre-covid literature was that — on average — workers enjoyed the opportunity to work remotely. Mas and Pallais (2017) ran an experiment where they offered various versions of call center jobs to applicants — some with the option to work remotely, and some not — and also varied the wages for these hypothetical jobs. On average, they found workers were willing to accept an 8% lower wage for the opportunity to work remotely. The large survey by Barrero, Bloom, and Davis largely confirms this finding too. On average, respondents value the opportunity to continue working from home after the pandemic at about 7.6% of wages.

On the other hand, Bloom et al. (2015) found that, after their 9-month experiment with working from home 4-days per week, half of participants chose to go back to their office and only 35% of staff who initially expressed a desire to work remotely ended up taking up the opportunity. Interviews suggested remote workers felt lonely being out of the office for so long. This matches the kinds of concerns that are raised in internal studies of Microsoft employees working remotely during covid-19: one study found “missing social interactions” was one of the most frequent challenges reported.

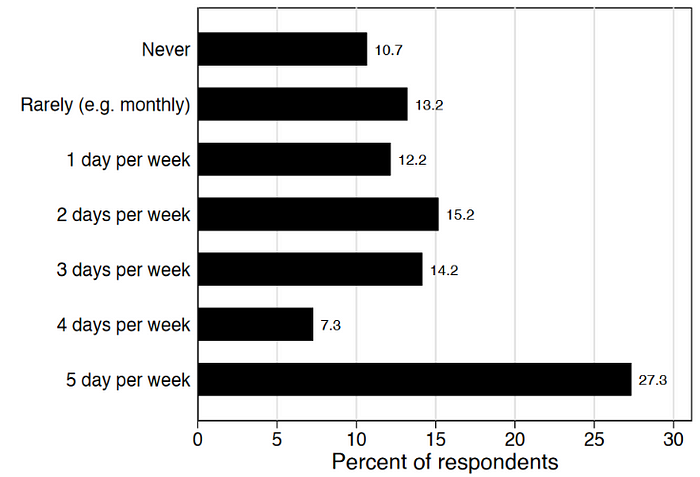

Moreover, while workers value the option to work remotely, the majority of them still want to go into the office some of the time. The following figure breaks down remote workers preferred number of days to be working remotely: nearly 50% prefer a hybrid option, compared to 27% who want to be fully remote, and 23% fully in the office.

Source: Barrero, Bloom, Davis 2020

2. Pre-covid beliefs about remote work were wrong but hard to correct

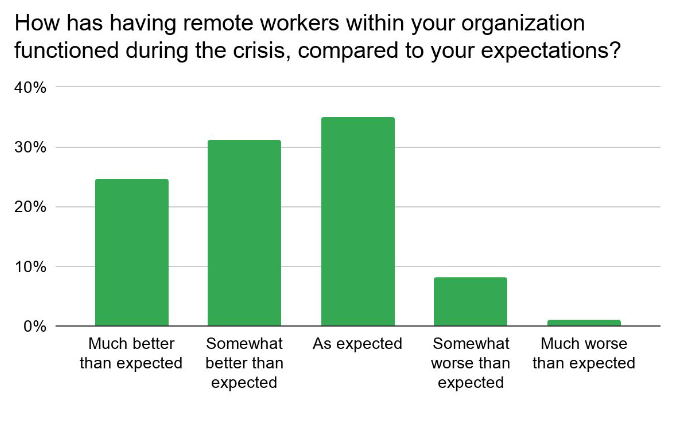

That said, if remote work is so productive, it is something of a puzzle why it was so rarely used prior to covid-19. Research on the covid-19 pivot to remote work provides some answers. Most importantly, perceptions about the efficacy of remote work were way off. Ozimek (2020) reports on an April survey of hiring managers that finds many more were underestimating the potential or remote work than were overestimating it.

Barrero, Bloom and Davis (2020)’s survey of workers later in the pandemic also finds consistent misperceptions about how well remote work would work: 19% said working from home was “hugely better” than expected, and 61% said it was better. Only 12.7% thought working from home was worse than they had expected.

So one reason remote work was not more common was that views on it were simply incorrect. But why did these beliefs persist?

First, correcting these beliefs by experimenting with remote work was not easy. Barrerro, Bloom, and Davis (2020) estimate the costs of adapting to remote work during the pandemic added up to about 14 hours of training per person, and $660 in new equipment investments per person. Moreover, a consistent theme across many internal studies of remote work at Microsoft was that experienced remote workers adapted with less disruption during the pandemic than those who were new to working remotely. Together, this means it is both expensive for a company to “try out” remote work, and that the full benefits of doing so take awhile to be clear.

Second, a study by Emmanuel and Harrington shows how, prior to covid-19, in at least one context less productive workers gravitated to remote work. This created a perception that remote work was inherently less productive, when the reverse was actually true. As discussed above, when covid-19 forced everyone in a call center to work remotely, Emmanuel and Harrington find the productivity of workers increased. They also show that, prior to covid-19, when the company offered on-site workers the option to work remotely, those who made the switch became more productive than they had been at the office. But, because the least productive call center workers were the ones who seized the opportunity to work remotely, on average remote workers were less productive than on site ones prior to covid-19. It’s just that remote workers would have been even less productive if they had been on site as well.

If these findings generalize beyond call centers, then it’s easy to tell a story where this kind of dynamic can be self-perpetuating. Suppose everyone believes remote work is unproductive and also believes this view is widely shared. In such a context, workers who want to climb the career ladder will tend to avoid remote work, to avoid the stigma of being lower productivity. This will ensure remote work is disproportionately performed by more complacent workers. This, in turn, might ensure that remote workers are — on average — less productive and reinforce the belief.

However, it seems covid-19 has broken this belief. As noted above, it’s no longer the case that most people believe remote work is less productive (surveys suggest nearly 90% think it’s as productive or more productive). Moreover, Barrerro, Bloom, and Davis also show workers believe the improved perception of remote work is now widely shared.

3. Concerns about social interaction and serendipity remain

While productivity has been, on average, unchanged or even improved by the shift to remote work, there are some signs that maintaining productivity and innovation in the long run faces additional challenges. One of the critiques of fully remote work has always been that it deprives workers of the social environment of the office which allows for clearer communication, the growth and maintenance of social networks, and serendipity.

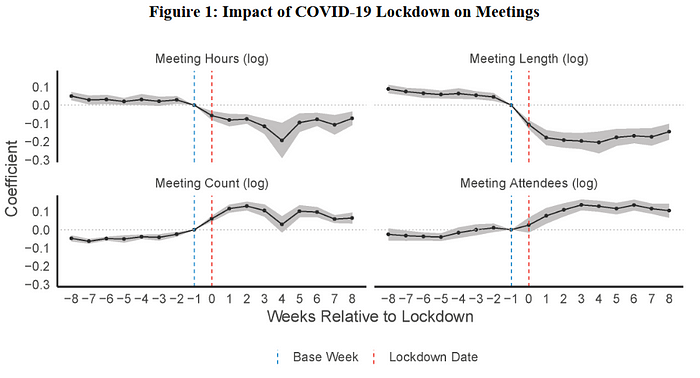

Several studies have documented how firms have adapted to maintain social ties in the absence of physical colocation. DeFilipis et al. (2020) document a shift towards more frequent, shorter virtual meetings with more people in the 8 weeks following the onset of lockdowns, perhaps as a substitute for hallway conversations and popping into offices for a quick chat. Espin and Rojas (2021) document a similar shift in the use of remote meeting technologies following covid-19 lockdowns (and also document a marked decrease in the audiovisual quality of these meetings as they are conducted via residential internet connections). Oz and Crooks (2020) provide evidence via a small sample study that workers substitute instant messaging for face-to-face contact.

Source: DeFilipis et al. (2020)

These alternatives for maintaining contact seem to have been effective at preserving pre-existing relationships among coworkers. An internal study by Microsoft tracking email, instant message, and phone calls of 92,000 employees both before and after lockdown found no decline in daily contact, and an increase in the size of the network of people contacted.

But all these forms of communication are purposeful; they require one party to purposefully arrange a contact with another. That makes them less useful for new workers who have not yet built a network of coworkers. A study of new employees at Microsoft Azure found less social connection (and lower productivity) than is typical of new hires in the office. More generally, all surveyed workers worried they were losing connection with “weak ties.”

Microsoft internal surveys also found remote collaboration technology was less suited for some kinds of work. Software engineers missed gathering around a whiteboard (a complaint echoed by an earlier study of distributed teams at Google), and found it harder to do big picture/creative work while fully remote. Others complained it was harder to plan, brainstorm, and change directions quickly in virtual meetings than had been the case on site.

4. Remote work will improve over time

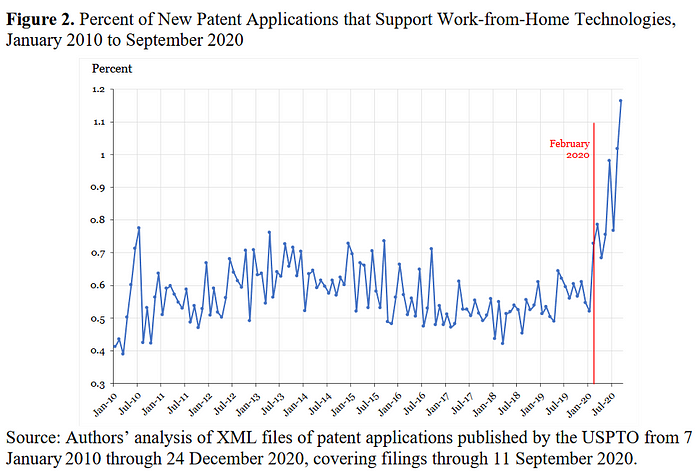

At the same time, we also have plenty of indications that remote work will improve. The fact that remote work appears to be likely to persist (see next section) has created a large market opportunity for improved remote work technology. Bloom, Davis, and Zhestkova (2021) document that the share of US patent applications that include words associated with remote work expanded dramatically at the beginning of 2020, as the scope of the covid-19 crisis became clear.

Moreover, internal studies at Microsoft consistently find that problems associated with remote work are less common among experienced remote workers. The same studies also identify various processes and policies that mitigate remote work challenges. For example, at Microsoft a more formal system of check-ins and 1:1’s with a manager helped reduce problems associated with onboarding, and explicit efforts to build community and social ties was beneficial for new hires. With better technology coming, workers gaining experience, and best practices being discovered and diffused, the experience of full time remote work is likely to improve.

Perhaps most importantly, many challenges associated with remote work appear likely to subside once the pandemic ends. Social isolation due to reduced contact with work colleagues is not being fully offset by out-of-office socializing, given widespread social distancing. Moreover, the clear preference for hybrid work over fully in the office or fully remote (though sizable support for the latter also exists) may allow workers to strengthen weak social ties and use in-person meetings strategically to perform tasks less well suited for remote work (like gathering around a white board or settling on the direction of a new project).

5. Remote work will be more common after covid-19 subsides

When the covid-19 pandemic eventually subsides, it appears quite likely that remote work will become significantly more common. In an April survey of 1,500 hiring managers in Ozimek (2020), 62% of respondents planned to make their workforce more remote than before, as a result of covid-19, with 26% planning to make their workforce significantly more remote. A May 2020 survey of 1700 small business leaders found 41% of respondents planned to let more than 40% of their remote workers stay remote when covid-19 ends; 17% of small business leaders plan to let nearly all their remote workers stay remote.

Lastly, in Barrero, Bloom, and Davis (2020)’s large survey of US workers, they ask workers how much their employers plan to let them work remotely when covid-19 ends. They use the responses to estimate 22% of all workdays will be remote after covid-19 ends, compared to just 5% of workdays before. Note that this estimate is conservative, because it assumes all employees who have not heard from employers about the post-covid remote work policy will be 100% on site. Workers would prefer to work remotely on 44% of work days.

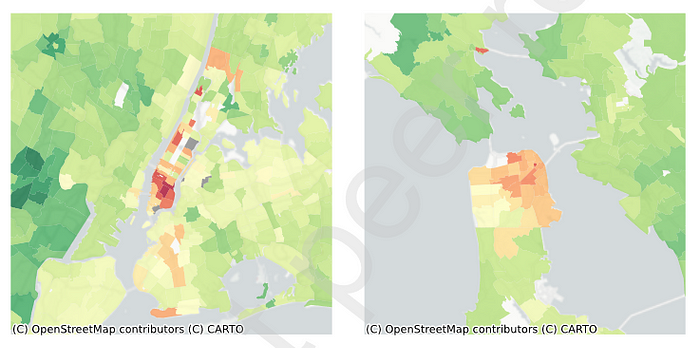

Survey responses that indicate wider use of remote work are also consistent with changes in property prices (though it is tricky to disentangle the effect of remote work from the effect of covid-19 here). Gupta et al. (2021) document that prices for new residential property has grown more quickly farther away from the city center than it has in the city center, during 2020. Indeed, in places like New York and San Francisco, there have actually been price declines in city centers in addition to price rises in the suburbs.

This reflects increased demand for living farther away from city centers. This data is adjusted for the quality of housing, so this does not simply reflect a desire for more space during social distancing. Moreover, Gupta et al. (2020) find this effect of rising suburban prices relative to city center prices is stronger in cities with a greater share of jobs that can be performed remotely. Interpreting suburban prices as a forecast of the desirability of living far from city centers for many years, this indicates a strong belief that the downsides of living far from the office are likely to be lower in the future than they have been in the past.

Gupta et al. (2020) is about relocating from the city center to the suburbs. In contrast, Brueckner, Khan, and Lin (2021) show (among other things) that you can see the same kind of thing happening across cities.

Cities with highly productive firms pay high wages, but in the era before widespread remote work, these workers needed to reside within commuting distance of the office, resulting in high housing prices. Brueckner, Khan, and Lin (2021) write a simple model to show that, given the opportunity to work from anywhere and keep their high productivity job, workers in these highly productive cities will tend to relocate to areas with lower house prices. This will tend to reduce housing prices in these high productivity cities where jobs can be done remotely (and raise prices in the cities being relocated to). They show that this is indeed what has happened since the onset of mass remote work. Using a sample of 792 different US counties, they show counties with high productivity workers and a high share of jobs that can be done remotely experienced slower growth in housing prices than otherwise similar counties.

6. The new equilibrium will have winners and losers, but will probably raise overall welfare

If remote work is here to stay, is that a good thing? With this major transition underway, it’s too early for the data to say. To think through the possible ramifications, we have to turn to models.

In 2020, economists have begun tweaking models of the spatial economy to incorporate new assumptions about the viability of remote work. Delventhal, Kwon, and Parkhomenko (2021) develops a model of the LA economy where workers vary in their ability to work remotely, and choose where to live and work (in LA). Another paper by Delventhal and Parkhomenko uses a similar model to understand the entire US economy, allowing workers to live and work in entirely different cities depending on whether or not their job can be performed remotely. Both models tie together a bunch of phenomena affected by decisions of where to live and work: housing prices, commuting times, quality of local amenities, and so on. Both then use actual data about all these things to calibrate their model, and then they see what happens when they change the model’s assumptions about the share of people who can work remotely.

Some of the predicted impacts are what you would expect. Consistent with the last section, on average, greater ability to work remotely leads people to move away from city centers to the suburbs, and away from larger cities to smaller ones in the interior. But some large cities with exceptional amenities (such as San Diego) see an increase in residents. Other superstar cities such as New York and Washington DC see the number of jobs associated with them increase, as more workers set up residence outside the expensive city and commute in occasionally, and because the price of downtown commercial real estate falls.

But their model also has a lot of fascinating second-order effects.

For example, in LA the rise in remote work leads to faster commutes for everyone who still needs to go in to the office. Less traffic on the roads means commuters can also afford to live further from the city center, since they can expect faster travel times during their commutes. There is also less pollution, due to less total commuting. Both effects benefit workers who do not work remotely.

More ambitiously though, these models take a shot at understanding the potential impact of remote work on agglomeration spillovers. Agglomeration spillovers is a name economists give to the productivity enhancing power of population density. What happens to these spillovers when a large share of the work force is not on site? Do they evaporate? If so, does that offset the benefits described above?

It’s an open question. Agglomeration spillovers are typically understood as stemming from many distinct microfoundations. To take one example, as noted above, there is some evidence that it’s harder to communicate some kinds of ideas remotely, and harder to build and maintain social networks. At the level of a single organization, these might have difficult to detect but deleterious effects on things like overall strategy, corporate culture, and innovation. These might, in turn have knock-on effects to other firms in the same region (since they may be expected to share workers and borrow ideas from each other). Weaker social networks might also hamper the efficient matching of the right worker to the right job. On the other hand, maybe these concerns are overblown; maybe we’ll get good at communicating online and socialize via twitter and occasional in-person meetings.

In Delventhal, Kwon, and Parkhomenko (2021), remote workers do not generate agglomeration spillovers, and so the increase in remote work reduces firm productivity. But it turns out this is just barely offset by suburban firms relocating their offices away to cheaper city centers. In their model, city centers tend to be inherently more productive and also to benefit from density of the remaining on-site workers. On the whole, workers are slightly better off and earn higher wages after the transition to remote work!

Delventhal and Parkhomenko’s model of the entire US economy is less optimistic, but considers a broader range of outcomes. In their most pessimistic scenario, workers only generate agglomeration spillovers when they are physically on site. In this setting, an increase in remote work slightly increases total welfare overall, but almost all of the gains flow to 100% remote workers, who benefit from being able to reside wherever they like. Most hybrid workers and 100% on site workers are worse off overall due to the decrease in productivity (and hence, wages) that happens in response to the unwinding of agglomeration spillovers. But Delventhal and Parkhomenko also consider the possibility that remote workers might generate some fraction of the agglomeration spillovers generated by on-site workers. In their model if remote workers generate about 60% as many spillovers as fully on site workers do, then this is enough to ensure that even fully on-site workers benefit from the increased use of remote work.

It’s still early days, and I have no doubt there is much more work to come on this. But my takeaway from these first passes at quantitatively thinking through the economy-wide impacts of remote work is that on the whole it’s a good thing.

If you think this is interesting, I have a free newsletter about recent social science research on innovation. Check it out here.